For MTRL, the Future of Materials Development Is about the Innovation of Meaning

Among Japan’s manufacturing industries, the materials industry is booming, boasting a high global market share and profit margin. However, the challenge of adapting to a fast-changing world presents itself as a major structural issue – one that ultimately may chip away at the industry’s growth.

How, then, do we innovate for its future?

To achieve breakthroughs in the materials industry, MTRL, a team at Loftwork specializing in business development support based on materials, technology development, and cutting-edge research, is embracing a design approach. At the center of this is a focus on the “innovation of meaning”; here, MTRL business manager Kazuya Obara makes a convincing case for why we look to the methodology, and how we can all implement it.

The Materials Industry Is Driving Japan's Economy

Japan’s materials industry is a leading industry with approximately 30,000 establishments, 1.2 million employees, approximately 56 trillion yen in manufactured goods shipments, and approximately 20 trillion yen in added value*. However, this growth cannot be sustained in the long term if we don’t consider the industry’s two major roadblocks:

- There are less and less issues to be “solved”. We live in a society in which consumer needs are constantly being met. How, then, do we propose new values in everyday life through materials?

- The speed of social change exceeds that of materials development. The world is changing at an unprecedented rate, yet it often takes 10 to 20 years to develop a material from the start of research to its implementation in society.

Until now, materials development has been driven by scientific and chemical approaches. However, we are entering an era where conventional methods alone may not suffice.

*”The Role and Expectations of Innovation in the Materials Industry,” Materials Industry Division, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, 2018

Finding New “Meanings” in Materials and Technology, MTRL-Style

MTRL (Material) was established in 2015 as a team specializing in materials and technology development under Loftwork. With our strong design approach, MTRL has been engaged in various development and co-creation projects centered around creating new values for materials and technologies. In addition to product development, the team has been involved in prototyping for the implementation of the circular economy, exploring new values in robot development, and planning and producing exhibitions.

Following the “Design Driven Innovation” model, as advocated by Dr. Roberto Berganti of the Stockholm School of Business, we don’t just stop at finding and solving a problem; rather, we try to look for the “meaning” that lies at the root of or beyond the problem.

The following three points are fundamental to our practice:

Changing the purpose of innovation: Until now, innovation has been framed around solving problems. We propose to redefine innovation as not only solving problems, but also creating new meaning.

Understand the usefulness of design thinking: Design is an attitude of asking “why”.

Practice design actions that stimulate material development: Utilize design that cycles between “how” and “why”.

Avoiding the “Innovation Dilemma”

For those of us accustomed to creating new businesses, innovation is often defined as a disruption – a situation that overturns an existing business, service, or concept. Today, many companies implement various methodologies, strategies, and tactics for innovation creation, but are quickly drawn back when they encounter an inevitable “innovation dilemma”.

The Dilemma of the Postal Carriage Operator

About 150 years ago, with the advent of railroads and automobiles, postal carriage operators, who had been the key to transportation, lost many of their jobs. These horse-drawn carriages simply could not compete with new technologies in terms of speed and operating efficiency. Could they have transformed their business by listening to their customers?

As it turns out, no. To borrow from Henry Ford, “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

In other words, when an existing business faces a major challenge, trying to find a way out of it based on customer feedback does not always result in new ideas and answers. While there is merit to customer-driven marketing and problem-finding, listening too closely to the customer’s voice can also risk miscalculating things. For mail coach operators, they could not abandon their old ways and turn to a completely new approach, even if they wanted to improve their business. This clearly illustrates the “innovation dilemma”, something still very much relevant today.

New Meaning Sparked in Candles

The modern candle is another case study worthy of examination. Up until the 20th century, candles functioned only as altar lights or emergency lights in case of power outages, but the development of electrical infrastructure and the availability of products such as flashlights effectively rendered this function obsolete. Candle sales dwindled, forcing many candlemakers out of the business around the year 2000.

However, as we know, candles are far from dead; in fact, candle wax is consumed ten times more than that of the 20th century. The answer, of course, is in scented candles.

What is significant here is that the starting point of the innovation acquired a value different from “problem solving”. With the birth of the scented candle, semantic values such as “fragrance” and “experience” were added to a humble substitute for light. If a candle manufacturer had asked its customers then how they could make people want to consume candles more, they would have received answers such as, “Make a candle that lasts 100 hours,” or “Make a candle that is not dangerous.” That approach would not have led to the reconfiguration in scented candles.

The “innovation of meaning” we are working here aims to discover new meanings in materials and change their value – just like these candles.

Value Discovery Process through “Innovation of Meaning”

In recent years, as various industries seek out breakthroughs and innovations, “design” is having its moment in the business world, and expectations for design thinking are at an all-time high.

While there are many different methods of design thinking, the main approach that has been practiced in the business realm thus far has been to discover problems among users in order to create new ideas, then solve those problems.

To realize the “innovation of meaning”, our “design-driven innovation” is one of the methods of design thinking. It is, however, completely different from the conventional approach mentioned above. We are seeking to create new meanings, oriented towards the creation of radical, semantic change.

By discovering applications that are completely different from those of the past, and by accumulating improvements in the value of products, services, and ideas, the meaning of the material is reborn. So, how can we achieve such renewal of value?

Innovation in meaning requires a process of critically sublimating ideas over and over again. We create value critically by going through such questions as, “Why do you want to create it?”, “Why is the society in which it is created necessary?”, “Why does it make us happy?”, and “What is the value inherent in you?”

“How” and “Why” Necessary for Future Technology and Materials Development

Materials development to date has been driven by the scientific and chemical approach of “how to make it happen” – i.eHow to make something strong, how to make something safe, how to make something numerous and stable. These “how” perspectives have enabled people living in the 20th century to produce and consume large quantities of convenient products that are indispensable to their daily lives. However, in an era of rapid change, it is clear that it is becoming increasingly difficult to create new values through conventional methods.

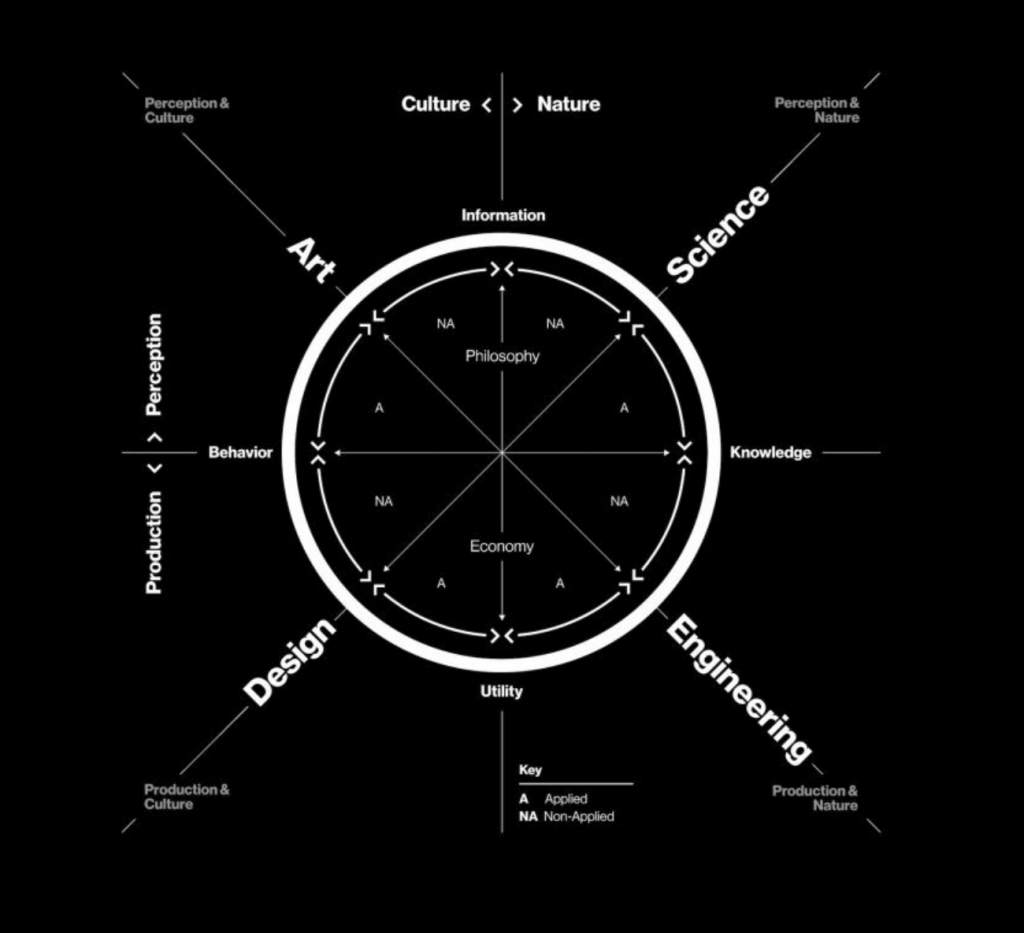

We are by no means dismissing scientific and chemical approaches, but rather, seeking new ways to effectively harness their power. The above diagram, created by Neri Oxman of the MIT Media Lab, alongside Joichi Ito and others, clearly illustrates this concept. It proposes how creative energy should be circulated in order to keep the economy circulating. We are advocating for the circulation of creative energy. The four axes depicted here – art, design, science, and engineering – serve a compass for the creation of new knowledge.

Broadly categorizing these four axes, engineering and science can be thought of as worldviews representing the “how”, while design and art act as the “why” starting point to find new perceptions and meanings in the world. We believe that this cycle of “why” and “how” will lead to the creation of innovative, new values not only in materials, but also in products and services.

To learn more about the more specific processes and practice of “innovation of meaning”, take a look at our project case studies: